This article was last updated on: January 2019

This Kiev and Chernobyl article is kind of long and thus is divided into four (4) parts. You are about to start reading part four (4). Choose here any other part you may want to go to: | One (1) | Two (2) | Three (3) |

ON MY WAY TO PRIPYAT

TO THE EXCLUSION ZONE AND BEYOND

Having explained more or less what happened in the accident, and why, it’s now time to describe my visit to the place.

Initially, you couldn’t go there, it was the delight of the Colombian taxi drivers resident in Ukraine when people asked them for a ride there. For those that don’t know, Colombian taxi drivers never go there.

Some people managed to go for scientific reasons, or the very few journalists allowed now and then.

On top of that, there were illegal but organised trips. They would get inside the zone through some places that weren’t so well-guarded.

In fact, this was a very active “industry”, in spite of the danger and the illegality.

In late 2010, Ukraine’s government chose to allow, and organise, legal excursions around well-known and not so dangerous places.

Of course, charging a fee for the privilege. The new legal visiting regime has been in place since 2011, that’s the one I had.

And for that reason, it’s not possible now to go inside some buildings you could go into before, among other things.

The government has an agency solely dedicated to the exclusion zone management, and it’s them that grant permission to those wanting to visit.

For this, they have to be contacted many days in advance with some documentation, and some specific requirements (and of course, the payment).

I’m not totally sure if you always need to go to them with a middle man, or what.

But not being a local, nor speaking the language (despite wanting to do so with a crazy passion), just passing by… The best you can do is to reserve with some agency that does the excursion.

That way, you avoid all that logistic nightmare and its potential headaches. It’s not only the permits, but also the transport all the way there, and inside once you have arrived.

The agency obviously takes its cut, but I think it’s legit.

They do everything, and the only thing you have to do is to be at a specific hour at a specific place of Kiev, have your passport handy, and dress according to the rules (it’s not about prudeness, it’s about radioactivity and things).

Granted, assuming you paid, and made the reservation with the due anticipation.

In my case, they even picked me up in the flat where I was staying in Kiev (the one I showed to you in part 1 of this article) for some extra money.

I happened to be staying close to the place where I was supposed to arrive if I hadn’t chosen to be picked up, but I had no idea.

I didn’t have an awful lot of time to find out, and back then I didn’t have a smartphone, just a basic mobile phone just in case.

I still wonder how did I cope without that thingamajig and how did things turn out so well when travelling around, all virginal and vulnerable in foreign and far away lands.

I can’t imagine going without it nowadays, but I have the memories of having done it, and survived the couple of times I got lost.

Fortunately, those were in Asia, where the Medellin invisible frontiers risk doesn’t exist.

When I travelled after getting a smartphone it was a quantum… leaaaap (look at my scientific jargon, loot at it dammit!).

The driver that picked me up arrived quite on time, and after greeting me, he made fun of me because of that. He told me:

–“You could have walked and you would have saved that money”.

I told him I had no idea where I was, and I didn’t want to risk getting lost for anything, and being left behind. He laughed and we continued our way.

Yet again, remember I didn’t have a smartphone nor a data-plan nor anything.

I could only have the information I would have found out before leaving the flat, and had I got lost, well, tough luck.

Anyway, it would have been a matter of just finding someone who understood some English, and was able to guide me. But again, punctuality was of the essence.

That happened to me in Shanghai and Tokyo at one point (as I told you), but in those moments I was relaxed with no specific time to be anywhere.

I even remember enjoying being lost.

But risking being left behind by the transport to Chernobyl, as little as that risk may have been? No way Jose!

So I had to mitigate that risk. And I paid more money to be picked up right at home, even though it was close indeed, and the laughter of the guy that picked me up was deserved.

I must have seemed like one of those lazy people who use a golf cart to move about the supermarket.

But anyway, we reached the place. It was to close to Maidan square if I’m not mistaken, and the rest of people started to arrived quite on time.

No one wanted to be left behind for not being punctual.

There were no Latinos other than myself anyway, so it wasn’t Colombia time when they tell you two o’clock, to arrive at four o’clock, and they think that’s normal, and even look funny at you when in fact you appear at two o’clock. Two is two!

And well, I’m everything but Latino when it’s about punctuality.

There, they gave me the dosimeter I rented for the day.

It wasn’t really necessary, since the guides already had and I wasn’t going to go where they told it was dangerous. I think I was the only person in the group to do that hahaha.

But I was very keen, and I rented my own dosimeter. There was even the choice to buy it, and I considered it VERY seriously.

The little gadget besides measuring radiation had an alarm to wake up and all, oh so good.

But I held back in the end, the middle class spirit prevailed.

Well, more than the spirit, I was held back by the middle-low class bank statement.

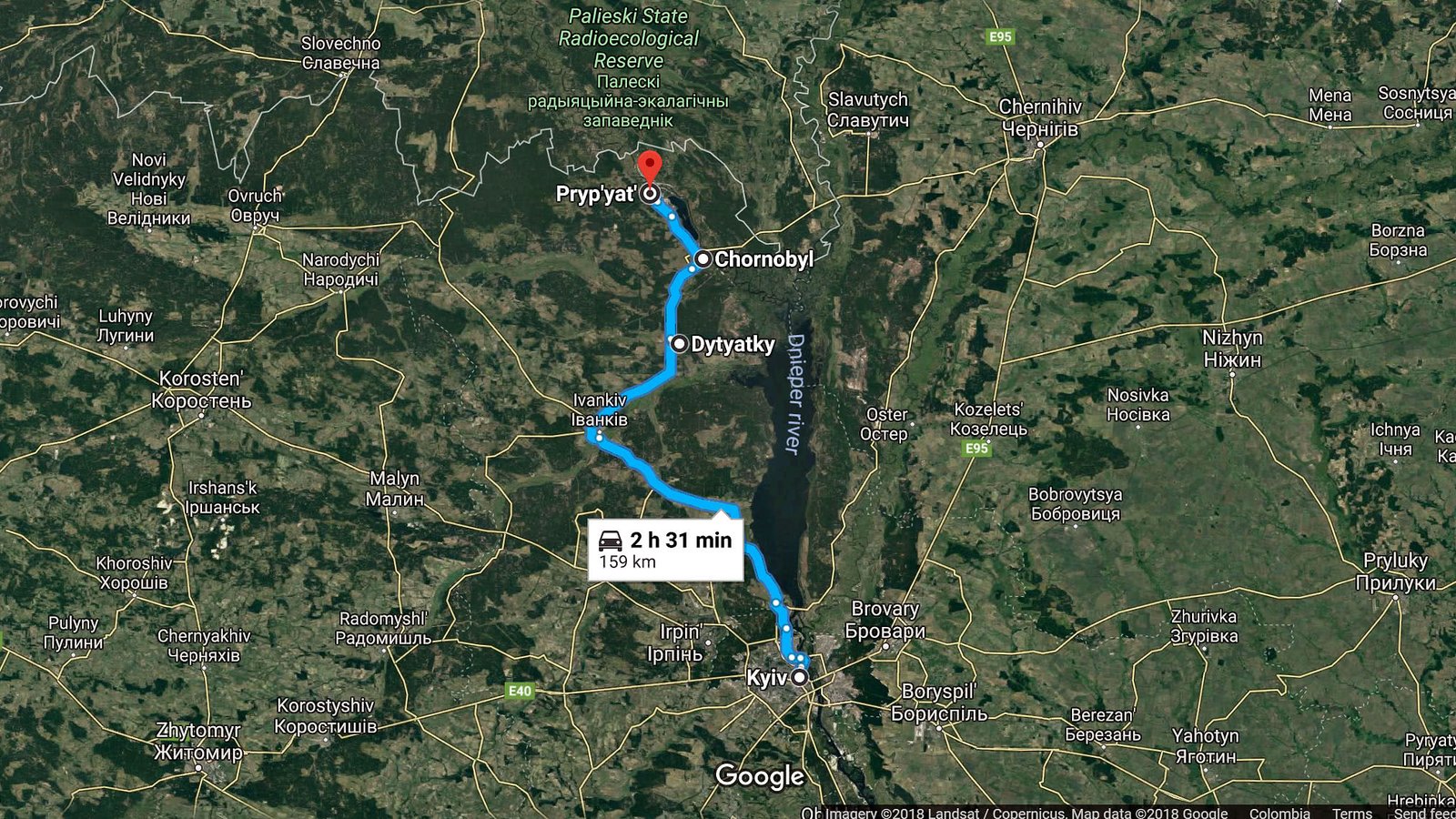

We boarded a very comfortable van, and off we went toward Pripyat.

Even though the power plant is known as Chernobyl, it’s actually close to Pripyat and not so much to the town of Chernobyl. This town still exists, and it’s inhabited.

Leaving Kiev.

Behind this dear friend somewhere along the road.

The travel time was of some two hours, or more.

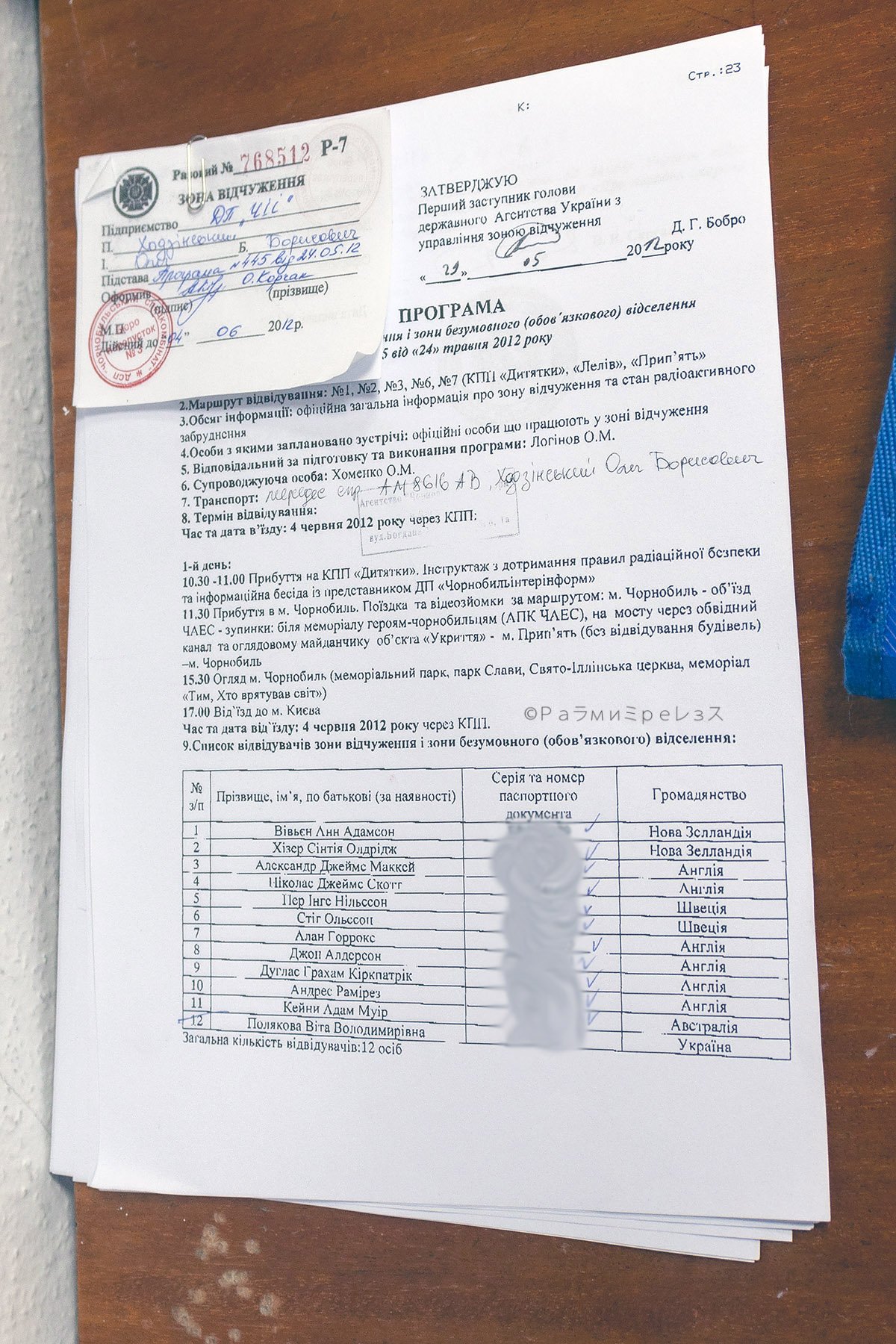

Before going in the exclusion zone we stopped in a checkpoint called Dytyatky, so the soldiers would see the passports, and do a general check.

Nick Rush-Cooper

The passports had to match the list of authorised people for that in the official documentation. Otherwise, there would be trouble.

Thankfully all was fine, and after the check we continued our way toward the exclusion zone and beyond.

—–

A little side note on the exclusion zone:

When Pripyat was evacuated, initially it was for three days. Nonetheless, people never came back.

On top of Pripyat, they evacuated an exclusion zone of 30 km, once they created it. There were a few villages in that radius.

But some people of those villages resisted being evacuated, and some others were evacuated but made a clandestine return to their homes for different reasons.

Those people technically made something illegal, but the government tolerated their return and lets them live there, even though they’re in a legal limbo by doing so.

The inhabitants are counted by the few tens, and their age is 65 years old in average.

These people are called “samosely”.

The oldest are the “originals”, but with the conflict in the Donbass there have been people who have left that region because of that war.

And a few of those people ended up living inside the exclusion zone because they can’t afford anything else inside the country.

These new “samosely” say they lead a tranquil life. That radiation kills them anyway, but they say they prefer it to a stray bullet of that war.

It’s yet another part of all this problem, and something the government must not be very happy about.

So, it’s illegal to live in the exclusion zone and most people was evacuated and never came back. But there are people still living there, for one reason or the other.

Little exclusion zone little side note end.

—–

We arrived in Chernobyl town, still inhabited, as I was telling you.

In the Soviet Union, the welcome signs to the cities or towns weren’t uniform, and almost always had something alluding to the main activity of the place or something it was known for.

Above is the Chernobyl welcome sign, I don’t think I have to explain why it’s like that.

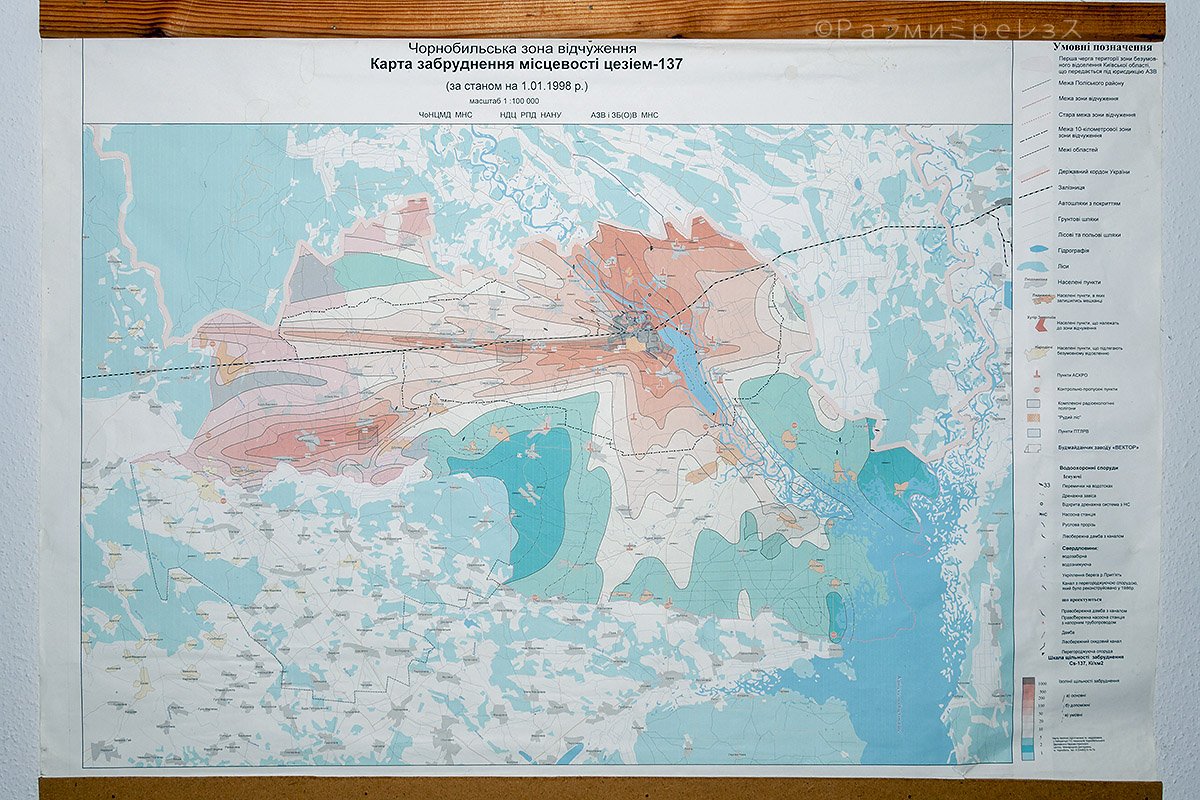

So, we sat there and they showed us some maps and told us what happened, they explained to us what we were going to do during the day, and they briefed us on safety.

In the photo below it’s shown what I understand to be the concentration in the zone of Caesium-137 that escaped from the reactor the day of the accident.

That isotope is a product of the fission process (process that I half-tried to explain with whatever little I may know in part 3 of this article), and it’s very toxic.

Because of that, it spread everywhere, and the more concentrated it is, the more dangerous. And hence the map.

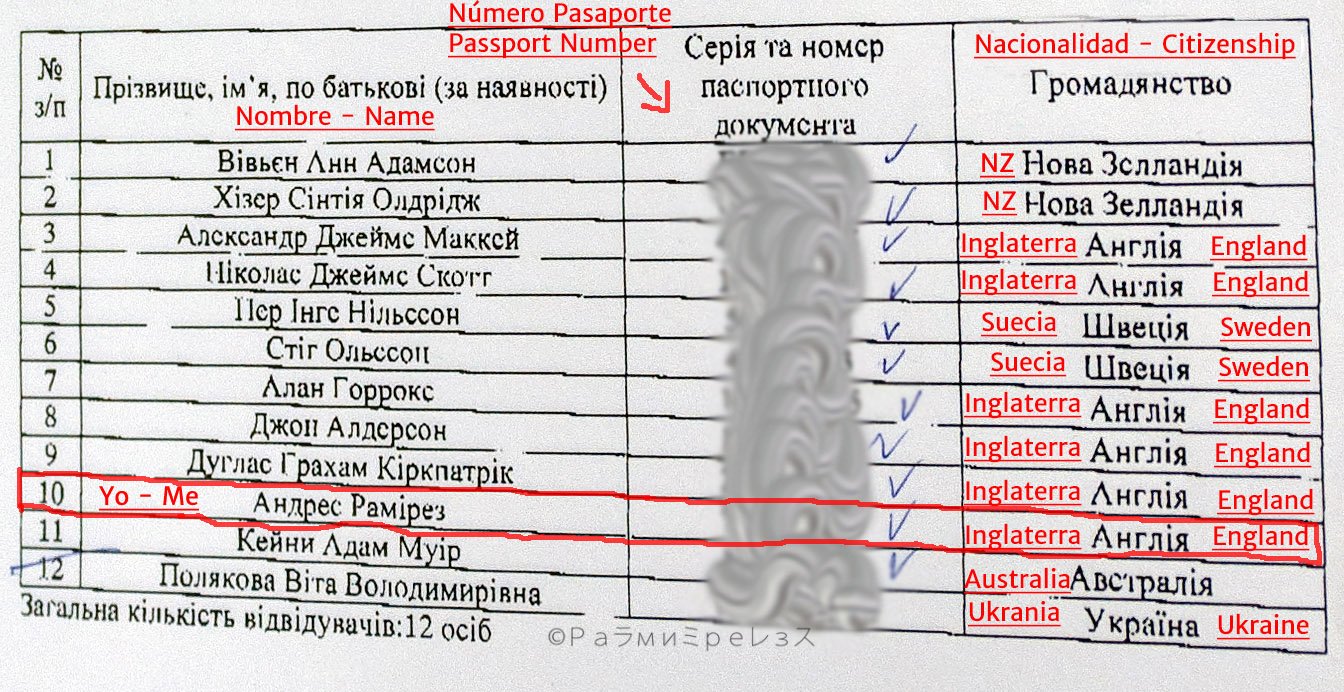

I also saw the sheet with the instructions. And another sheet with the authorisation, the information asked by the government, and the group member list.

In my group, the guide was Ukrainian, and the official citizenships of the visitors were: Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, and United Kingdom (England literally, but that passport doesn’t exist. The United Kingdom’s is the existing one). Seen below.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Once we understood the instructions, we started the tour.

Of course, there were many rules to follow, but the guide and the driver weren’t particularly strict or annoying. Quite the opposite, in fact.

PRIPYAT

WHERE EVERYTHING HAPPENED

Pripyat was a “model” city in its time, built in 1970 on purpose, so the nuclear power plant employees and their families would live there.

Of course, it also had other services and companies, but the core of its existence was the nuclear power plant.

Back then, those jobs were considered very good and desirable in the Soviet Union, and thus, the city was quite modern and comfortable in its context.

By the moment of the evacuation the city had some 50.000 inhabitants. Now the place lies totally deserted, and nature has “sucked it” little by little.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Doggyyyy.

Nowadays most people who have anything to do with the exclusion zone live in a town called Slavutych, and well, Chernobyl town as well, as I was saying.

We started, and initially we reached the monument to the liquidators (that I mentioned in part 3). It says in the plaque:

–“To those who saved the world”.

Then we saw some of the robots they tried to use to clean the roof of the reactor, but that didn’t work because of so much radiation (which gave way to using the “bio-robots”).

When we left the place with the robots, we arrived to a monument to World War II.

That monument had been there since before the accident.

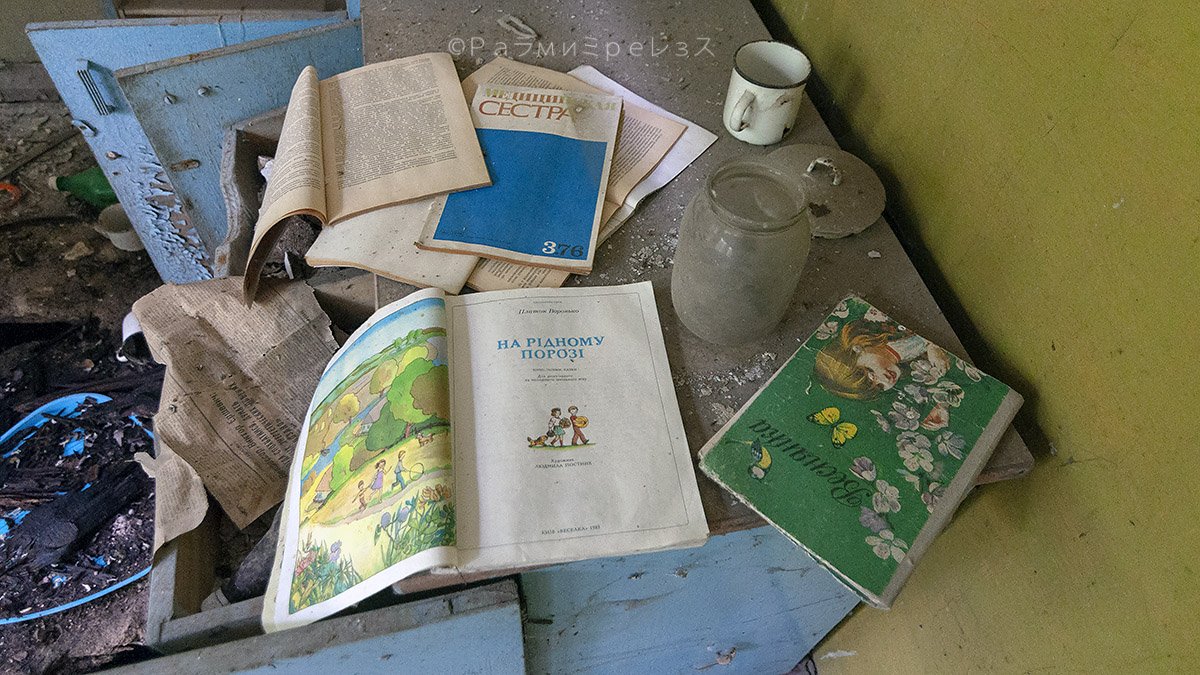

We visited a kindergarten in a place called Kopachi.

Kopachi was a little village that was evacuated after the accident, and then destroyed with bulldozer and buried. Literally.

The only thing that survived that was the kindergarten.

It still has dolls, toys, and books from the time that were left behind after the forced evacuation.

Going in.

It says there “parents corner”. The typical board for parents.

Casually measuring radiation from that teddy.

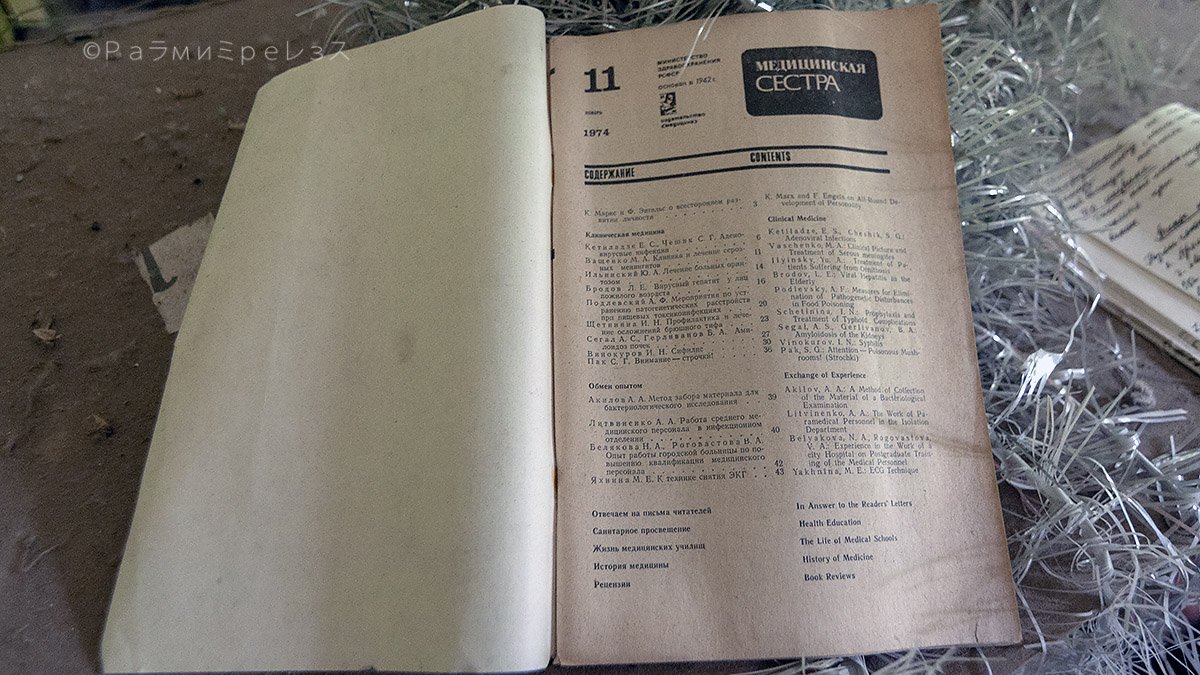

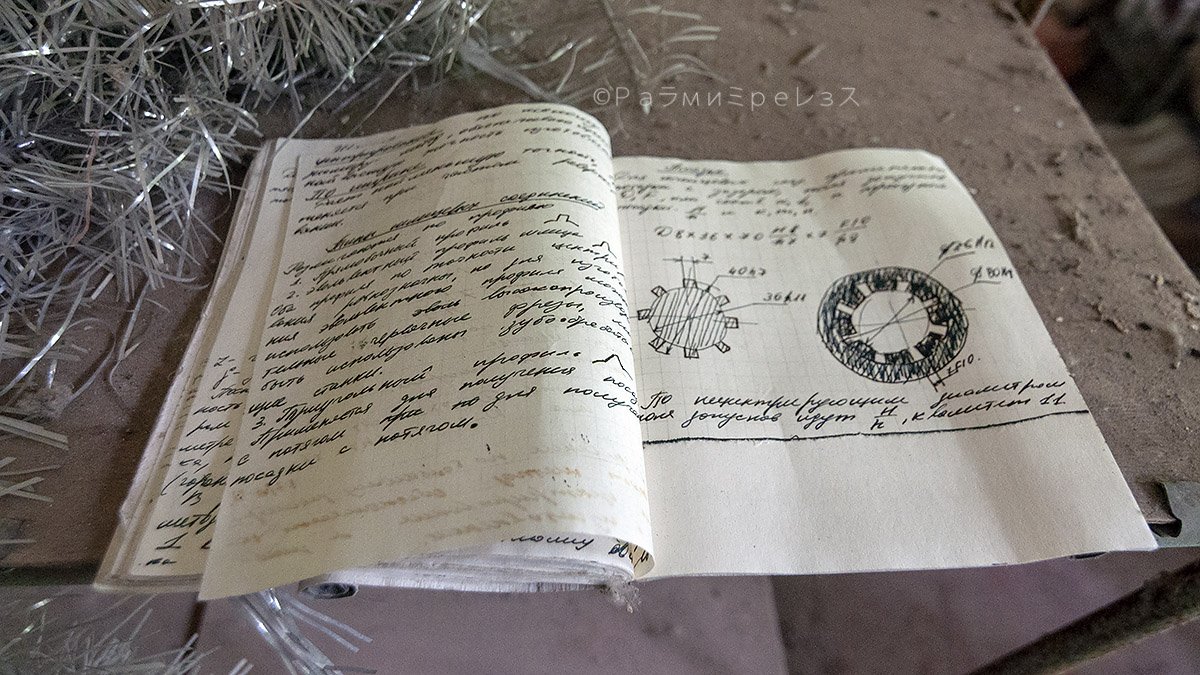

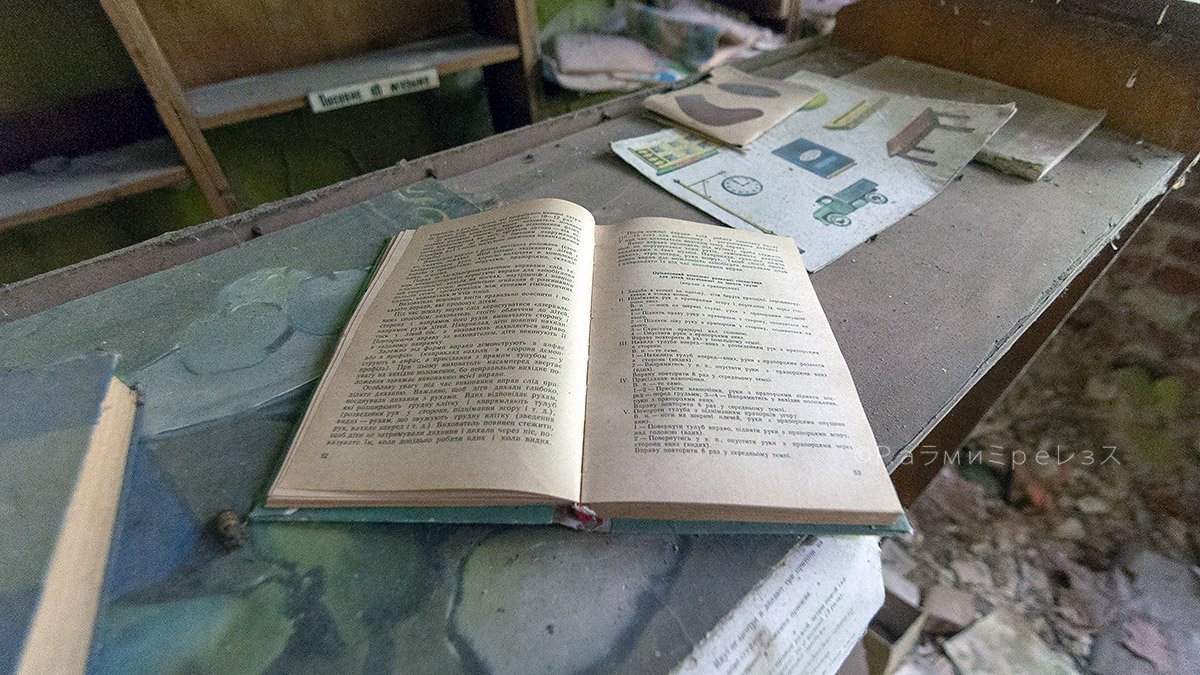

Books and notebooks.

Another abandoned toy.

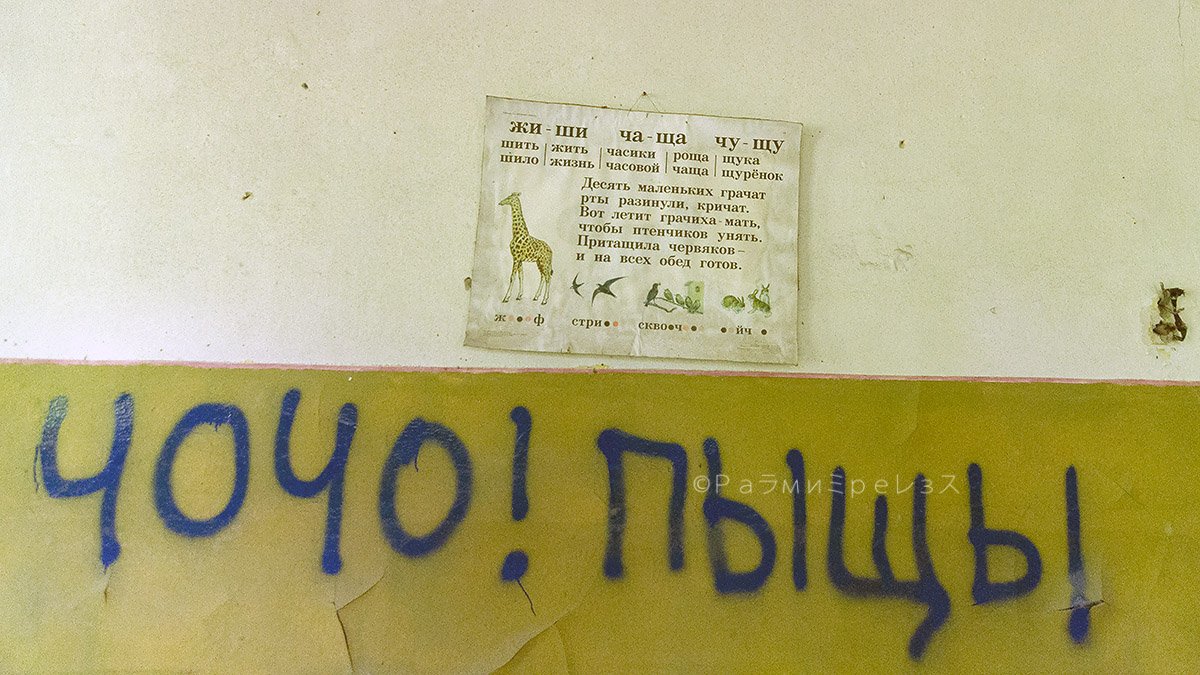

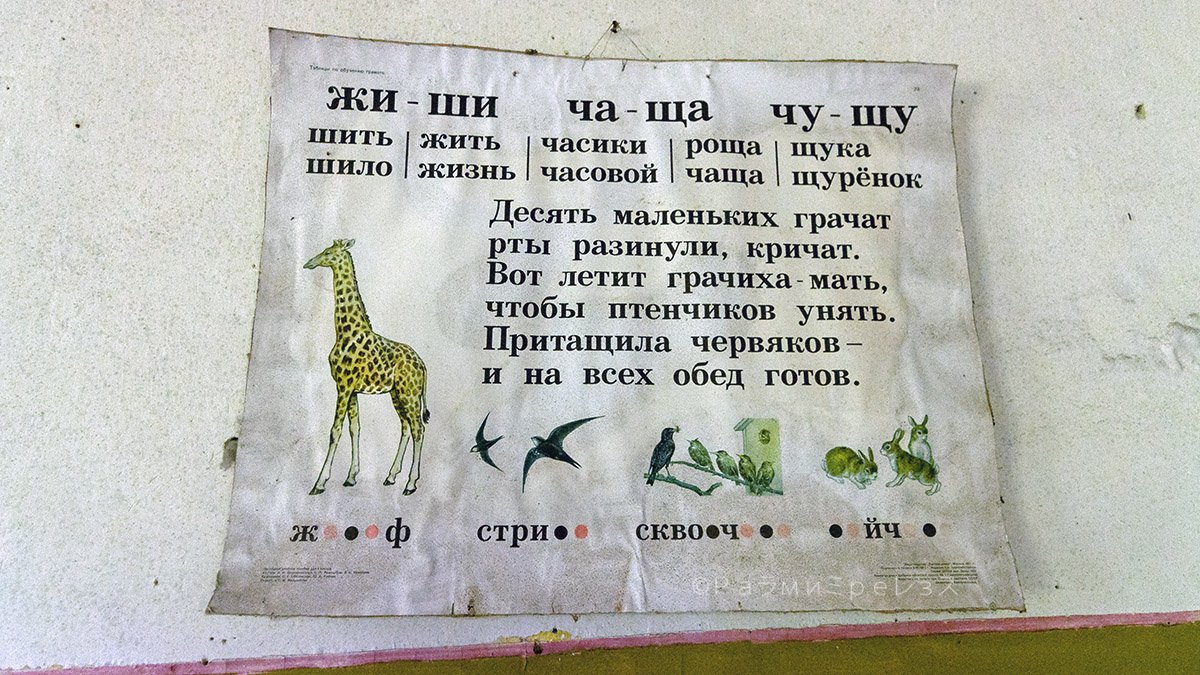

Learning to read and write with the giraffe.

More abandoned books.

Books.

Ramírez.

Measuring radiation by the entrance.

I played with my dosimeter between one place and the other, there in the photo below the dose was quite low.

When it increased it came to a point where it started to beep and flicker.

On our way to the next places we had in sight part of reactor number 5.

Reactor number 5. This reactor was never finished, although its official cancellation came only in 1989, three years after the accident.

Cooling towers.

Reactor number 4, the one of the disaster, in the distance.

After some minutes we reached Pripyat.

Casual in Pripyat’s welcome sign.

You can see it’s different to the sign of the town of Chernobyl. As I tell you, signs weren’t uniform, they were just tailored to the town or city.

No idea about that bus.

We entered the town close to the rail tracks.

Buildings “sucked” by nature.

A cross, one of the first things I saw.

Ramírez.

Close to some sort of pier close to Pripyat river we walked by a building that had a sign in its roof that precisely said “Pripyat”.

Apparently it was a very famous café in town.

While I was walking by certain places, the guide would lend me some photos, and would tell me:

–“Look, this place was like this before the accident”.

I could recognise some places just by some references, but in others it was very noticeable what they had been.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

In the first photo of the gallery below the Prometheus statue can be seen, in front of the town’s cinema.

The statue was moved to a memorial that I will talk about later.

Pripyat before and after.

Soon enough we reached the river shore.

The river is behind the vegetation.

Measuring the radiation in the river.

Time doing its thing.

There’s a 16 storeys building that used to be residential. It has a big Soviet star in the roof.

Soviet Star.

“Dead don’t cry”.

Ramírez.

The cinema “Prometey” (“Prometheus”) was a very popular place in Pripyat back in the day.

People there would come together to see films, or simply to gather socially in the café it had.

What’s left of the cinema Prometey.

Part of the exterior.

Interior.

It says there “entry to the cash register”.

This used to be a music school.

I walked by a building with a nuclear hazard sign and the word “Complex”, with some letters of the sign fallen to the floor.

I’m not quite sure what could it have been in its time, I think it could have been a city administrative building or something like that.

It had a faded sign that said something like:

“Specialised company in management and decontamination of radioactive waste.”

So, I guess the building had that role after the accident happened, and it was the headquarters of some team that made some important task.

But no idea about the role it had in Pripyat before the accident.

The Polissya Hotel, other of the tall buildings they had in Pripyat.

Right after the accident it was the headquarters of the liquidators, and the coordination centre with the air support.

This one below was “Palace of Culture ‘Energetik'”.

They had events, concerts, and sports competitions there.

Close-up to the signs.

This was the amusement park. In theory, they were going to inaugurate in May 1986. But May never came for the people of Pripyat.

There I am right underneath the ferris wheel.

Some versions say the park was inaugurated hastily after the disaster so the people could be distracted, and there are some photos that allegedly are from the park already opened.

The park, especially the ferris wheel, has become a symbol of the accident.

It even appears in a very famous video game called Call of Duty 4. I think it was the last Call of Duty I seriously played, by the way.

I had that game and I beat it, and when I was in that ferris wheel I remembered everything. Especially the main“villain” saying in the intro:

–“Our so-called leaders, prostituted us to the west”.

The scene can be seen in the video below.

Not only that. The park has very different radioactivity levels.

For instance, the pavement is safe. In part, it was the liquidators that cleaned it in their operation.

And in part, I was told, that material “sucks” radioactivity (but I don’t know about that for a scientific fact. No idea).

Look at these photos below the place where I have the dosimeter (over pavement) and the amount of radiation it registers:

1.28.

You can walk relaxed. But on the other hand, vegetation doesn’t “suck” radioactivity like that (I don’t know about that for a scientific fact either).

And so, radioactivity levels increase suddenly in a matter of centimetres, all proved with my rented dosimeter.

Look again at these other two photos, the placement of the dosimeter (on top of the vegetation, just centimetres away from the pavement where I put it before) and the radiation it’s registering now, and compare with the numbers above:

¡19.27!

In the amusement park was where I had more fun with the gadget, fittingly.

In the video below I’m very close to dangerously radioactive vegetation, with the dosimeter beeping and alarming, and as soon as I retreat toward the pavement the thing calms down.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

This sign belonged to a restaurant, perhaps a buffet.

I can recognise some words in those blue signs such as “fruits” and “sausage”.

Pripyat firefighters’ station.

Those firefighters were the first responders in the catastrophe (and the first to suffer the consequences). Some of the very first liquidators.

Firefighters station interior.

This was laying in front of the entrance to the firefighters station. Better not to get too close, I think.

Would it have been a firefighters car?

The jail.

A jail cell without flash.

A jail cell with flash.

REACTOR NUMBER 4

EPICENTRE

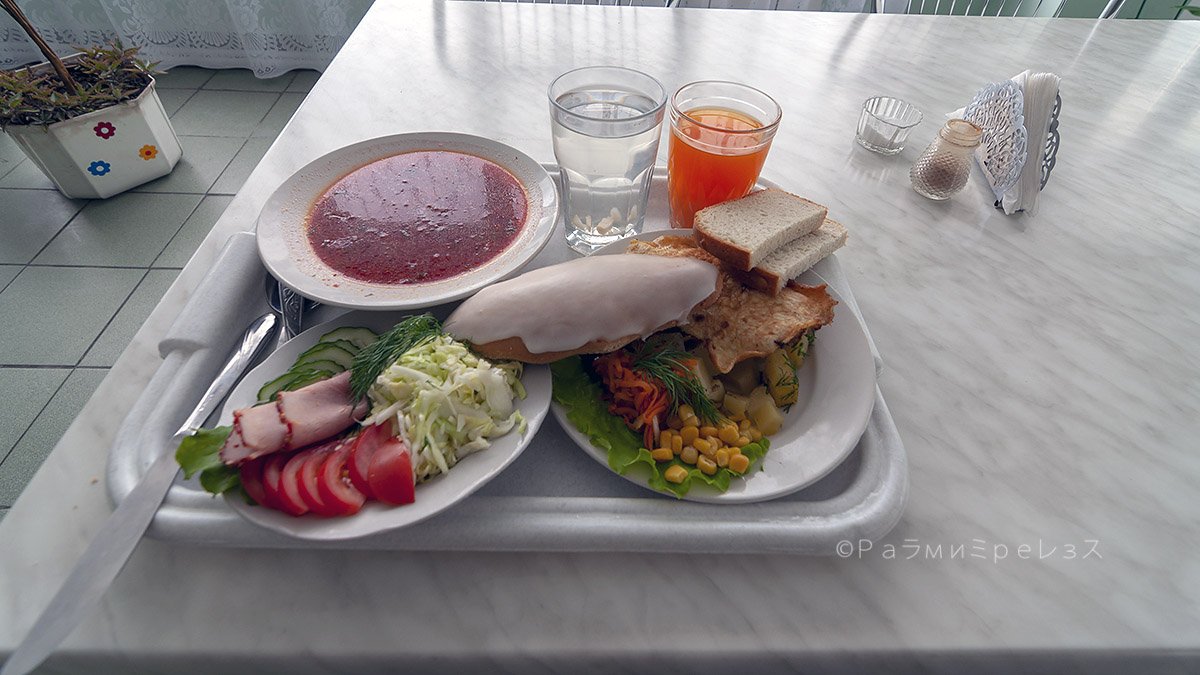

We interrupted the tour to have lunch.

After that we would go see a memorial, right the place where they put the Prometheus statue that was in the cinema.

And after that, we would go to the reactor number 4, the disaster one.

We had lunch in the place where all the workers do it.

Kittyyyyy.

When going in or out they measure your radioactivity levels with a machine. If you’re good, then it’s all OK.

Radioactivee I am.

They don’t do that only there, there are many filters from the exclusion zone.

Now, if for any reason you went beyond the allowed level they have to treat you before you can leave the zone.

If the machine was activated by a material object you have, they determine if they can clean it.

If it can’t be cleaned, tough luck, you need to abandon whatever it was (shoes, watch, what have you…). It’s not optional.

They measure that with a science-fiction special machine.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

The lunch was plentiful, and I don’t remember it being bad at all.

I had already eaten borscht in Moscow, a traditional soup from Russia and East Europe. I repeated in Pripyat (it’s the red soup).

After lunch, we continued. I walked on top of a train bridge, below it there’s part of the reactor’s cooling lake.

There are many live fishes there that you can feed if you want to.

I don’t think anyone catches them, for obvious reasons.

Those fishes can be giant, and there are many urban legends about it being because of the radioactivity.

In what I’ve read, that isn’t the reason.

They simply don’t have predators, but they have food, so in those conditions they grow much more than the fishes of the same species that live in normal ecological conditions.

There is a story about a train bridge, even though I’m not sure if it’s the same I was walking on. I don’t think it is.

The thing is, they say that the night of the accident there were some people there in a train bridge.

When the accident happened they kept looking toward the reactor, the beautiful colours it was showing them, and the “show” it was giving them.

Well, when it all exploded the wind took the radioactive cloud toward them, and none survived. Since then, the bridge is called “the bridge of death”.

Going further, I reached the black statue I’ve talked about so much. It’s the Prometheus statue.

As I mentioned some paragraphs before, in the beginning the statue was in front of the town’s cinema. The cinema was called precisely “Prometey” (“Prometheus”).

When the accident happened, they moved it in front of the Garden of Remembrance, a memorial they built to remember some of the victims.

In the Garden of Remembrance there are some plaques with names of these accident victims that I’m mentioning, and a wood cross in the back.

It’s a place that has been visited by heads of state of Russia and Ukraine, as you can see in the photo below.

It was jointly visited there by Dmitry Medvedev (Russia) and Viktor Yanukovych (Ukraine). Do you remember Yanukovych from part 1 of this article?

Kremlin

In Greek mythology, Prometheus represents the ingenuity, the inventive.

He stole the fire from mount Olympus, and gave it to humanity, making Zeus get mad (Zeus was mad at all times anyway).

With fire, humanity could advance a lot in many areas. So in some way, the statue represents the human ambition to progress, especially in science (and maybe what can happen if things go out of whack in that yearning, too).

After passing by that place, we reached the closest place to the reactor number 4 that we were allowed to be.

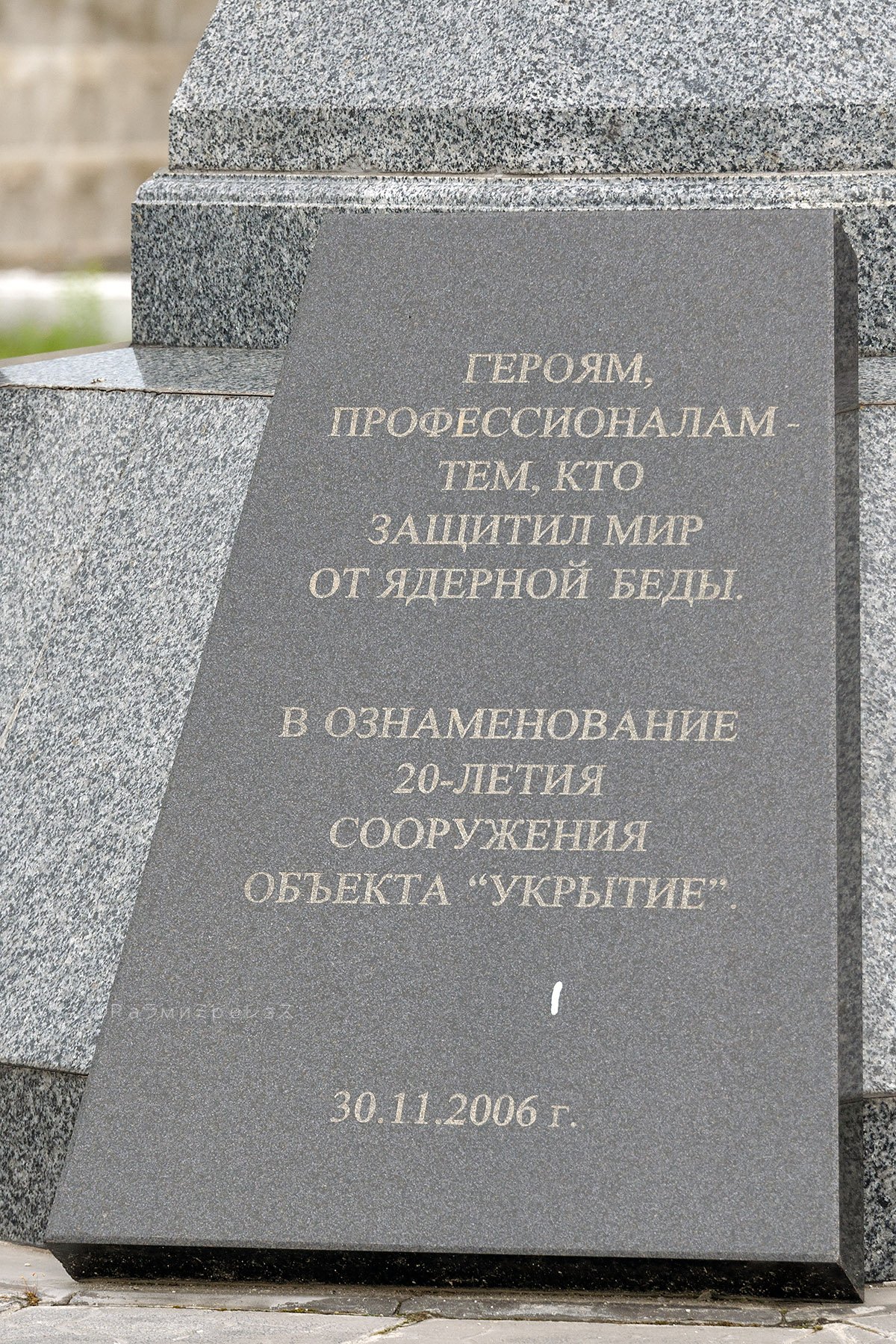

It’s a small square, where the monument to the builders of the sarcophagus is located. From there, we could see the reactor number 4 with its sarcophagus.

Indeed, radioactivity increased a lot there in that place, according to my little device.

In the photo it can’t be seen because it was already beeping with the high dose alarm, and when it did that it flickered. And well, I took the photo when it was in the phase in which the number didn’t appear… And I didn’t take another photo with the number visible.

It was spine-chilling to be there, have all that in sight, and know what had happened.

Those experiences make me reflect for real. Not Christmas, or any such mumbo-jumbo.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

According to an online translator, it says there:

–“To the professional heroes that defended the world from the nuclear calamities in commemoration of the twentieth anniversary of the building of the ‘shelter’ object.

November 30th 2006.”

It’s still useful to half-read Cyrillic, even if only to be able to use an online translator because I understand zilch of what I read hahaha.

“‘Shelter’ object” is the official name of the first “sarcophagus”. The one I had, before the Novarka’s NSC.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

Ramírez.

This was the end of our trip to Pripyat and the reactor. After that, we returned to the town of Chernobyl.

Leaving the sector, I saw a huge Novarka sign.

It must have been the place where they were preparing the NSC, the new and modern sarcophagus, that at the time of writing this is all but ready and installed.

On our way to Chernobyl town I was measuring radiation, of course.

Arriving.

There I bought a fridge magnet, and we visited another memorial.

Ramírez.

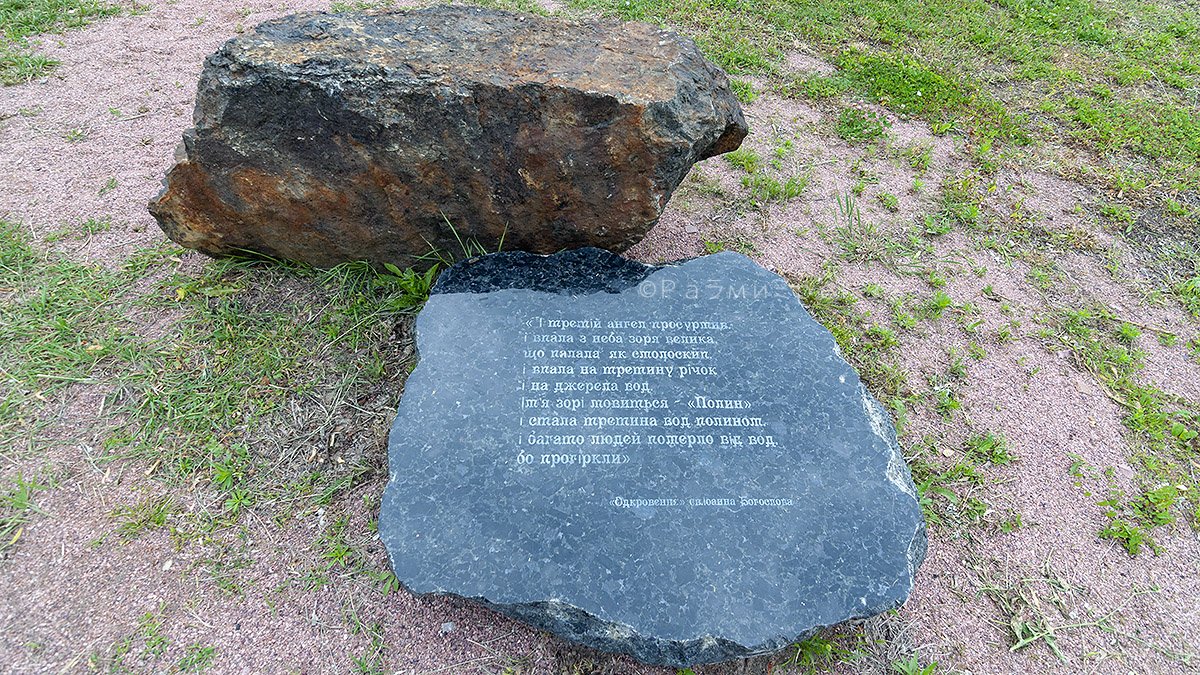

There was a statue of an iron angel in that memorial, that pointed to a stone with something written in it, I think it’s a bible verse.

Ramírez.

There is a path with signs on its sides. Every sign represents one of the villages that disappeared because it had to be evacuated.

After that, we made our way to Kiev again.

To finish this part, and the article, I leave with this gallery of photos that I took right there in the visit. I haven’t used these photos to illustrate anything of what you have read.

Take a look at it, it may be interesting.

Other photos of the visit to Pripyat, the reactor number 4, and the town of Chernobyl.

And well, we started our way back, and we were in Kiev a couple of hours after.

I went to the flat quite satisfied. It had been an incredible day.